April 2025:

Scent Map of my Yarn Wall

I put it here just because .

Poster for LJMU PGR Event

Mar 2025:

May 2024:

April 2024:

March 2024:

So we're back to the confirmation process.

My first draft helped me find a new research question: What is decentralization and why is it important. My second draft will be seeking to put my voice into the work more, which includes my practice.

Current readings:

- Strike art: contemporary art and the post-Occupy condition by Yates McKee

- How to Blow up a pipeline by Andreas Malm

- a whole bunch of abstracts about decentralization in lieu of the fact that there is no overarching theory of decentralization

Exhibitions visited:

- transfeminisms: Chapter I: Activism and Resistance. (2024) [Exhibition] Mimosa House: London. 8 March–20 April 2024.

- Unravel: The Power and Politics of Textiles in Art. (2023) [Exhibition] The Barbican: London. 13 Feb — Sun 26 May 2024.

- Women In Revolt! Art and Activism in the UK 1970-1990. (2023) [Exhibition] Tate Britian: London. 8 November 2023 -7 Arpil 2024.

February 2024:

So I am coming off of my 3 Month Leave of absence. I took the time to make work to reflect changes that came about due to changing supervisors and shifting nature of the PhD project.

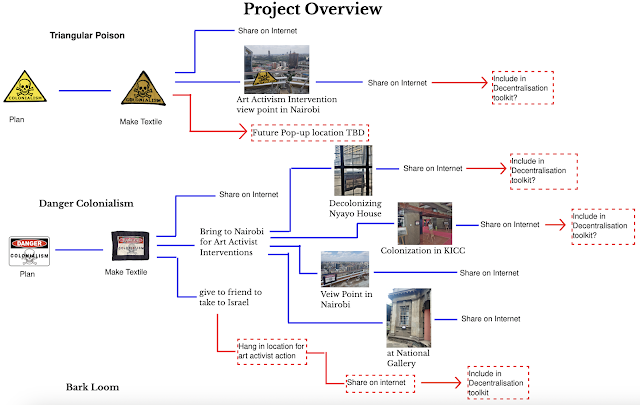

Danger Colonialism:

Bark Loom:

Interventions:

September 2023:

Workshops as a Means to Decentralise Art Activism

Research Question:

In order to decentralize protest, I will facilitate workshops to ask the question: can textile workshops be an effective tool for decentralizing art activism?

Decentralization: what it looks like in Art Activism and How I Plan to Decentralize

When I say that I want to decentralize art activism, I am wanting to increase access in terms of location, timing and risk, so that people who do not live in major metropolises, or who work nights or shifts when most protests happen, or who for various reasons are not able to risk possible arrest that normal protests may present, can still engage in artistic protest. Not all of my decentralization strategies will encompass all of these interest groups. My own challenge to participation in activism is location, I used to live in a major metropolis in Canada and now I live in what is technically a city in Germany, but is a very small and insignificant place.

Within art activism, workshops are prevalent, two of my art activism literature sources were intended as workshop material (Boyd and Mitchell, 2012; Duncombe and Lambert, 2021).

Some are even utilized with the intention of decentralization. The Center for Artist Activism, operating out of New York, holds workshops all over the world to share artistic activism principals with activists. (Duncombe and Lambert, 2021). This decentralization has taken art activism out of a few cities worldwide[1] and has helped bring it to many more cities.

Decentralization can work in many ways. Lindy Richardson’s Politics in Stitch: giving prisoners and students a united voice project (Richardson, 2019) managed an aspect of decentralization through centralization: part of the project involved inmates stitching banners that were used at the head a celebratory procession of women having the vote for 100 years. The inmates are centralized in prison, a physical centralizing that lacks power, power being a form of centralization, thus they are decentralized within a central location. Their stitch work allows elements of them to travel or decentralize, and then they are recentralized through their crafting, at a head of procession, a place of power. Decentralization is very much a theoretical concept, which can involve literal decentralization, but as Richardson’s project displays, it can also involve the opposite—a physical decentering can be a psychological centering. Richardson’s project was decentralizing because the inmates did not have to travel for their voices to be heard.

Creating protest banners for others to march with is also used with Aram Han Sifutentes’ Protest Banner Lending Library project(Han Sifuentes, 2016; Sifuentes, 2021). Han Sifutentes held workshops for vulnerable people who are unable to protest due to arrest fears to create banners that are then lent out and used at various protests. The project allows for both literal and psychological decentralization, the banners can and do travel to various protests and are made by people who are non-centres in society—people with precarity, often with tenuous immigration status as Han Sifutentes herself used to be.

My project Protest Pin Workshops uses workshops as a method to decentalize art activism and protest textiles. While Han Sifuentes’ project might be seen as shadow protest (insert reference to my chapter on shadow protests), the art activist and craftivist workshops mentioned previously are not active protests, but training or protest item creation for protest. My project envisions the workshop as a place of active protest. Participants craft a textile pin or accessory within the workshop that is then gifted, mostly through mail, to a public figure to encourage them to make good choices to mitigate the climate catastrophe.

The Efficacy of Protest

Protest has the efficacy of riding a bike across a dry sand beach. Protest is not about results. Even so-called successful protests tend to have moderate gains over years or even decades-long campaigns, like ending slavery, decolonization, women’s rights. Even smaller gains such as wage increases at a national chain[2] can take multiple years.

One protests because they hope. One protests because they believe they must. One protests to change themselves and each other. One protests on a hope, a prayer, with breath held because maybe, just maybe, this will be the brick that makes the walls crumble. There has never been one march that changed the world, Rosa Parks refusing to sit in the back of the bus did not end segregation in the United States, the #metoo movement was the spark that ignited after countless failures.

How to Determine is My Research is Successful

Protest is not about direct results-based efficacy, but my workshop method as a way to decentralize art activism still requires verification of successful. What would success entail? To draw decisive conclusions from the workshops, participants will answer a questionnaire to find out if they have or will send out the pin they made, if they are more likely to engage in art activism in the future and if they are from a category of people with less access to protest that is seeking to protest.

Summery of Preliminary Results

The preliminary results from the 6 person workshop shows promising data workshops may be a good method to decentralize art activism: 75% of the participants mailed the pins they made at the workshop. While only one participant felt it was quite likely that they would send more pins and two felt it was possible. Art activism was promoted through the workshop. 50% of the participants had engaged in art activism previously, 5 of the 6 participants felt they were quite likely to engage with art activism in the future and the last participant felt they were more likely to engage with art activism after attending the workshop. As the group was comprised entirely of artists, it is not surprising that the participants would express their intentions to engage in an art activism with their own methods.

[1] Originally most practioners were based in New York or London in the English-speaking world.

[2] see craftivist project (insert reference to that project) that was successful in getting a retailer to join and pay a fair wage, after two years of an unsuccessful protest campaign.

August 2023:

Workshops as a Means to Decentralise Art Activism

Premise:

Art activism has become legitimized and commonplace, and protest is frequently concentrated around centres of power in, for example, major cities organized by established international NGOs. In order to decentralize protest, I will facilitate workshops to ask the question: can textile workshops be an effective tool for decentralizing art activism?

Within art activism, workshops prevalent, and some are even utilized with the intention of decentralization. The Center for Artist Activism, operating out of New York, holds workshops all over the world to share artistic activism principals with activist and artists and expand the locations where these activities are practiced(Duncombe and Lambert, 2021).

Decentralization can work in many ways. Lindy Richardson’s Politics in Stitch: giving prisoners and students a united voice project (Richardson, 2019) managed an aspect of decentralization through centralization: part of the project involved inmates stitching banners that were used at the head a celebratory procession of women having the vote for 100 years. The inmates are centralized in prison, a centre lacking power, their stitch work allows elements of them to travel or decentralize, and then they are recentralized through their crafting, at a head of procession, a place of power. Decentralization is very much a theoretical concept, which can involve literal decentralization, but as Richardson’s project displays, it can also involve the opposite—a physical re-centering can be a psychological decentering.

Creating protest banners for other to march with is also used with Aram Han Sifutentes’ Protest Banner Lending Library project(Han Sifuentes, 2016; Sifuentes, 2021). Han Sifutentes held workshops for vulnerable people, who are unable to protest due to arrest fears, to create banners that are then lent out and used at various protests. The project allows for both literal and psychological decentralization, the banners can and do travel to various protests and are made by people who are non-centres in society—people with precarity.

My own project workshops using mailing as a means to decentralise protest textiles within the field of art activism, also uses workshops as a way to decentalize art activism and protest textiles. While Han Sifuentes’ project might be seen as shadow protest, the rest of the workshops discussed are not active protests, but training or preparation for protest. My project envisions the workshop as a place of active protest. Participants craft a textile pin or accessory within the workshop that is then gifted, mostly through mail, to a public figure to encourage them to make good choices to mitigate the climate catastrophe.

Project History or where Ideas Come From

The idea of workshops comes from a call that I answered seeking craftvists to be a part of the world environmental history conference in Oulu, Finland in 2024. The group of us that answered the call decided to be the convenors for a panel, a maker space and a workshop. We divided into two groups, with the maker space and the workshop being organized by myself, Dr. Anna Svensson a reseracher at Upsalla University and Dr. Verena Winiwarter a professor at The Austrian Academy of Science, who was also the instigator of starting a craftivist panel at the conference.

Throughout this process, our trio had many ideas and conversations, but it took a while to find the right idea. Dr. Winiwarter shared some literature with us about the idea of mourning ecological degradation (Barnett, 2022), which reminded me of the mourning armbands project that I was already in progress with. The concept of some sort of mourning Jewelry was decided and agreed upon for our workshop at the world congress of environmental history conference. We decided to present the idea of craftivism and the mourning accessory (a gender neutral term to use in place of jewelry) in the workshop and then each provide a different project for participants to choose. My own contribution would certainly be a pin or brooch, that could, like my mourning armbands, be mailed.

At this point within my research, I had been trying to find methods to decentralise art activism. The idea of workshops was already something that was prevalent in my mind, two of my art activism literature sources were intended as workshop material (Boyd and Mitchell, 2012; Duncombe and Lambert, 2021) and workshops are a prevalent within craftivism. It was apparent that using the same method as my mourning armbands, mailing, would yield a practical way to host a workshop that also functioned as protest. The workshop would not simply train individuals how to make art activism, but would actually involve activism. The art activism workshops are training and the craftivist workshops are making prior to protests, but my workshops as conceived could work as protest-in-action.

Moving from Ideation of an Idea to Certainty in that Idea

Conceiving of an idea is relatively simple, but having that idea also withstands scrutiny is more of a challenge. My idea is that I would hold workshops to make pins to mail to public figures to encourage them to make good environmental decisions and these workshops would function as a method to decentralize art activism. The idea of using workshops, as previously mentioned, is a proven method. The efficacy of these workshops will be addressed later, after the idea is proven to be sound.

But why a pin? Is it the ideal format for this protest? Fundamentally there is no ideal way to protest—some people will never be moved to change their opinions and actions. While this pessimism might seem misplaced here, an unneeded aside that disrupts the flow, it is important to remember protest is and always will be fighting against the odds. Pragmatically a pin works, it is small enough to be made during the course of a workshop as well as being able to be mailed in an envelope. Pins are also functional, as I come out of ceramics I understand the importance of functionality—functional items are something people can conceive of, that they can understand. Pins have a history of being political. I have a collection of pins and buttons from when I was younger, some of which are political because political buttons used to be fairly common. Former USA secretary of state Madeleine Albright used brooches to convey political thoughts during her political career and the queen used a brooch to display her contempt of then president Trump. Textiles are also important because of their element of care—both in the making and for the recipient. It would be possible to get a button maker, spend an afternoon and make hundreds of pins, but these pins would be devoid of the care that is in the textile. Gifted textiles are blankets, sweaters, knit accessories and baby clothes; they are often handmade intimate items gifted to a loved one. They are created slowly with care and thoughts of whom they are being gifted to. There are ample reasons to choose a textile pin, but is mail a good delivery method?

While choosing mail was a repeat, it is perfect for this project in terms of decentralization. Mail allows the senders to protest while remaining anonymous[1] and avoiding risk of imprisonment. One target group in terms of decentralization is people with arrest concerns. The workshops, at least some of the planned ones, would also be decentralized in terms of location, happening at events people travel to or taking place online. Mail is also something that everyone has access to, which would allow workshops to take place online. While mail has a cost factor, one or two letters are within reach of most people. If participants want to continue making pins after the workshop, this is something they have access to. Participants can also choose to send items digitally or in person.

Public figures that have the ability to make environmental decisions are targeted. Everyone is encouraged to pick people that are local to them. Major companies CEO’s or members of government are examples of public figures and everyone has a local member of government that usually has information that can be found through googling.

Sending the pins to public figures would be a form of gifting. Gifting is a devise that craftivists also use. It is a way of creating relationship between the giver and the receiver, and if accepted, it creates obligations that the receiver should fulfill to giver.

The pins are being made to try to get better environmental choices to be made due to the climate crisis. The original idea was for an environmental historian’s conference, so the environment was the obvious choice for the conference. However, the climate crisis is the largest pressing issue facing our world now, so using it again is logical. It is also an area where most people in higher positions of power can make decisions to improve climate mitigating actions. These are actions that can be made on most levels of authority. This means that participants can pick almost any public figure of authority to send a pin to.

The last part of the idea is that the workshops would work a means to decentralise art activism. The decentralization factor was discussed with regards to mail. The initial idea holds us to scrutiny, there is reason to believe that holding workshops and mailing protest pins, as previously described, might be an effective method to decentralize art activism.

Test Method Workshops and Questionnaires

But would these workshops actually work? Would participants want to mail the pins after they had made them? The only way to test the efficacy of the workshops would to be hold them. Not all artistic research requires traditional research methods. It is possible to simply use arts-based methods in conjunction with source reviews and contemplation. Even a workshop might not require data from participants. It would be possible to hold the workshop and draw conclusions from the results, but the best way to draw definitive conclusions would be to question the research subjects, who will be called participants. In order to draw complete conclusions from the workshops, participants will answer a questionnaire to determine factors that keep people from protesting, to ensure a good sampling of at-risk people to see if the workshop might effectively work as a way to decentralize protesting. A series of workshops would be set up with a pilot workshop in order to improve the workshops.

Sampling as a method to perfect workshop pin styles

The style of the pins that participants made still needed to be determined. My own practice is predominately weaving, but embroidered pins also seemed like a logical choice. I worked through both ideas, with several iterations of embroidered messages. A globe was created by cutting out some garbage bag and sewing the edges with red thread onto a grey felt. The result was stunningly beautiful, which then negated the message in it. It also took around two hours to make. I also mocked up some slogans where I embroidered the letters on felt with embroidery thread. Deciding what messaging to pick was not easy and the embroidery was slow, with most taking me an hour to create. I also did some mockups for weaving, using cardboard looms and plain weave. As I am aware how seductive plastics can be, bubble wrap looks beautiful when woven, I stuck with a black palate, using garbage bags and garbage bags mixed with wire or wool. With wide strips, I could weave the fastest in ten minutes.

But which to pick? Pragmatically the weavings would be better because the embroidery might take too long. My main concern was would people connect with and want to make a woven pin. I suspected that people would connect with the embroideries as they resembled political pins bumper stickers and patches, which they would be familiar with, and they would also allow the creators to pick messaging they identified with. When trying to discern what might be the opinions of others, the best method is to ask someone. I consulted a collogue, who had invaluable advice and set me on the path to making woven pins.

Weaving aligns with my practice. Ideologically being able to use scrap materials is also much more compelling. The weavings would have an opaqueness to their meanings, with a fluttering message. This porosity would allow a level of confusion in the recipient, as it is less easy to classify and mentally store away. The momentary confusion, the pause, allows for connection—it gives the brief space to contemplate the pin. While the meaning of the woven pins has openness, they would be accompanied by a note that explained the materials and the desire for the recipient to make good environmental choices. Weaving would be the primary activity of the workshop, but examples and materials could also be provided for any who wished to work by themselves on an embroidered pin.

A Workshop to Workshop Workshops

Workshops can be thoroughgoingly researched, planned and thought through and still not be ideal. The best way to plan a workshop is to have a mock or pilot workshop in order to better plan a fully fledged workshop. As research subjects take time to line up, they are not an ideal test pool. However, my fellow classmates, who somewhat align with my ideal workshop candidates, are excellent pilot subjects for my research. The workshop organization, time management, room set-up, and skills can all be assessed. The questionnaire can be honed in order to ensure clarity, comprehensiveness and appropriate length.

Pilot Workshop: Transart Residency in Liverpool

Setting up

Once a year most transarts students meet in Liverpool at LJMU to hold sessions in person. My workshop was scheduled for week two for this learning period. While there are many students during the first week of this get together, the second week is more sparsely attended. Four people signed up for my 90 minute workshop, one said they could not attend, while others told me the day before that they planned to come. I expected 6 people, planned for 8, but made 10 printed copies of all paperwork just in case. My workshop was planned for 1:30, but because the activity prior to lunch was scheduled to end late, the lunch break was very short so I expected people to be late. I had been collecting plastics during my time in Liverpool and had also made a trip to the beach the day prior to the workshop to collect washed up flotsam including things like rope. I also had cardboard saved for me, much more than I needed.

In the morning of the workshop day I set up the room and printed off my documents. Printing transpired to be incredibly difficult. I did not manage to print any of my documents myself and had to e-mail them to a school technician to print. In doing this the formatting changed and one part of my questionaire sat awkwardly on the page. So lesson #1 is to always print documents the prior day and recheck formatting.

[1] There is a very minor possibility that finger printing could be used in order to find the identity of the sender. All attendees are made aware that there can be dire and unknown consequences to all protesting activities.

July 2023:

I've been doing some mock-ups for textile pins for my workshop at the transart residency. The workshop is:

An experiential Introduction to my research: A workshop to make a protest textile pin.

In this workshop, we will be making a textile pin or broach on the theme of the climate crisis. Participants will be encouraged to pick a public figure to mail the pin to, that encourages this person to make responsible choices regarding environmental policies. The workshop will end with filling out a questionnaire and a short discussion on using traditional research methods for an arts-based practice.

I created this globe using old garbage bag sewn into felt with red thread. I was working off of a globe I had a photo of on my phone, so consiquently the globe slipped a bit. That is minor and would be possible to fix, the real issue is the fact that it looks so lovely. The red stitching, rather than giving a danger vibe just makes the dark earth look beautiful.

Embroidery slogans are the easiest for people to grasp. They resemble protest placards, bumper stickers or pinback button badge, that most people conceptually understand. While they look simple, they are slow. They take me about an hour. Having templates for the writing, and some tricks could make them faster, but they will take at least 40 minutes per badge, which is slow.

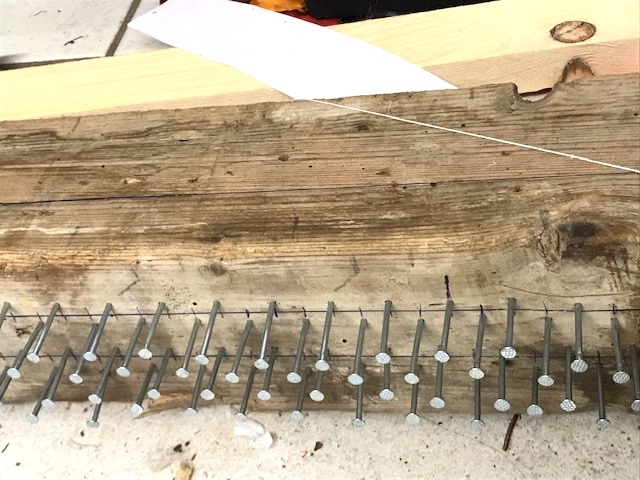

The last style I am going to look at is the black woven pins out of plastic and other discard material. I cut out simple carboard frame looms, which I managed to weave 2-3 badges on. One had 7 warp threads, one 6, the warp threads run the long way. For warp I used both a canadian black wool I’ve had stockpiled for years and cut up garbage bags. For weft, I used the ends of the warp at least once, plastic bag strips, packing strap strips and electricity cords. The weaving took 10-20 mins. I attached the pins by weaving through mostly with the plastic bags, but also with the wool yarn.

This is the style I will be working with. I chose it because it is fast enough, and it aligns with my practice. It is and will remain somewhat ambiguous. When the notes are written, the materials will be mentioned, but the meaning will be open for interpretation.

The colour black was chosen and will remain at least as the primary colour. I have done a lot of weaving and some hooking with plastics, bubble wrap, saran wrap, package banding, etc and it is really easy to make it look pretty, almost automatic. If it looks too nice, the message that waste is a problem is lost. With the black they are slightly less an object of beauty.

I will provide some examples and materials for the embroidery slogan style for those who do not like the weaving and wish to work on their own. I will see if this interests anyone.

May 2023: theming my PhD around decentralisation

The fundamental reason I make art is to break the rules. It pretty much always has been. In high school in my last year, right before writing my final exams I was making ceramic mugs instead of studying—at that point I owned my own kiln, I did not need to make them in school rather than studying, but I chose not to care. I had no intention of failing, but the unwritten rule to excel and to value excellence, I broke.

I do textiles, weaving specifically, because there is a lot of rules and I brake all [most? many?] of them. I was once told that my work is like Saori Weaving which is a type of weaving referred to as weaving without rules. My work is interesting because there are rules, without the rules, the work is slightly tepid. The is excitement in rule breaking.

I like to brake material or technical rules and I like to brake stupid societal rules. That is why I am drawn to protest. Breaking rules and systems, rules and systems that are inherently unjust and corrupt—that ooze like a festering wound.

And I am doing a PhD, a practise-led art PhD. Only, I don’t know, for the scope of this research degree, what my practise is. What specifically is my research? I am on a search to narrow down and define this. What is possible and appropriate within a PhD context?

An overall identified theme is introducing a specific field that does not exist, at least by name or as a separate ideology: Protest textiles. But, as this is not an academic research degree that is intending to delve into minutia of this new field, further specificity is needed.

A proposal was to do decentralisation of protest art [textiles]. With a secondary inclusion of shadow protests, protest ephemera and simulacra, which was included because it peaked the interest of a supervisor. They are correct that it is an interesting area that is understudied, but it is not active protest, at best is semi-active. This is not what I want to create. My view of what is protest art will likely not match that of my supervisors, as artist and academic Alana Jalinek stated “I used to think I was an activist and then I met some” (2013 p 1). I, however, know I am an activist, I have met plenty and been accepted by them as a fellow activist. The intention is to make protest art, not art about protest or art adjacent to or within a movement. While an attempt within the writing has been made to define protest art, I am a rhizomatic thinker. The definition will transcend sections, it will also be displayed best when cogitating upon different art.

Within this theme of decentralisation, four distinct projects were proposed as well as two semi-related conference workshops. But upon consultation with supervisors, it was suggested that each of these projects were PhD’s in and of themselves and that PhD’s required more depth. The mourning armband project seemed appropriate and feasible with the caveat that the project evolved. I absolutely could not spend three years criticising galleries, though I would be happy to add further allies like libraries to the list within the armband project. I am also not interested in funerary art (I took an art history class on the topic in undergrad and my personal project involved at looking at art-using-death rather than look any more at any funerary art). Post-apocalyptic art is also something that I am not particularly interested in. So I am left with looking in depth into many ideologies that I have only a passing interest in.

A consultation with the institute director gave me some further insight: get rid of the projects you can live without doing. Excellent advice, however, that only removed one project. Even when deciding to focus my PhD project on the mourning armband project, I still intended to do at least one, if not two of the other projects on the side. Which is fine, but maybe stupid? Why would I want to laser focus on a project that has a lot of side elements that I am not particularly interested in, while making art that excites me and not include it? I can follow rules, I just find ways to brake them while following them. So, where to go from here?

My personal goals for my PhD are:

1. To introduce the discipline of protest textiles

2. To find methods to decentralise art activism [or protest textiles]

3. To clearly define what protest art is and is not

Not only are these goals, but they are all original research, all gaps. None of them have in-depth research.

A material studies project I like to set myself sometimes, when weaving, is to create difference from similarity. I like to start with one long warp and use varying wefts to see how different the pieces can look. And I think that is what I have done with my PhD. It looks scattered and different, but it is not really. At the core is the same warp: Methods to Decentralise Art Activism.

Admittedly, the projects are set up to be a survey study rather than in-depth research. It would be possible to pick one method and study it ad nauseam—digging ever deeper and revealing further insights while doing so. The value of this depth is less relevant when the overall objective has no firm research, when no papers have covered the topic and artists, while they may have utilised decentralising methods, have made no study on this topic.

Why decentralization? I live nowhere. Technically it is a city, but only just.

Is decentralizing a framework that is helpful when looking at weaving? Traditional weaving is mostly decentralized. Aesthetically, if a blanket or shawl is considered, it usually has a top border and a bottom border and there is a pattern (or plain weave) that often runs to the edges, or there may be side borders. The top and bottom borders may be plain, but usually edge borders are decorated, often even more so even then the middle pattern. The top and bottom often have fringes. This is frequently the case throughout most of the world, other than some rugs and tapestries. This means that aesthetically, whole weavings are primarily decentralized. They have traditionally been created decentrally, with most households creating their own weaving. Globally weaving has taken place almost everywhere, with golden periods in terms of techniques and craftsmanship likewise scattered globally and throughout various eras. If a process of decentralization can be perceived as breaking borders, then it is possible to examine the expansion or demise of the selvedge.

The first major experiments in removing ideological as well as physical borders from weaving would be the 1960’s textile artist such as Magdalena Abakanowicz and Olga de Amaral. These artist brought textiles away from craft into the realm of fine art while exploring three dimensionality, industrial materials and monumental scale. Since that time, weavers have been exploring pushing the boundaries: in three-dimensionality like Marilyn Piirsaul and Kadi Pajupuu; with industrial materials like Brigitte Dams; through ever evolving collaborative installation like Line Dufour; and by weaving across literal national borders like Tanya Aguiñiga.

What does decentalization in weaving mean to me? Is it possible to decentralize a weaving? If warp and weft threads were removed from the middle, rather than being decentralized, the weaving would be re-centralized, because the lack of centre would draw attention to it. Though I have a set of weavings that might count as a literal decentralization. I did a series of untethered weavings, waffle weave structures that were loose, sometimes to the extent of not retaining the weaving structures. The waffle weaves were intended to be very deep, 50-100 warp threads deep, but with the added looseness, the depth increased astronomically, some of them were over ten times deeper than they were wide. During weaving, this depth originally was the centre, but after being removed from the loom, it was no longer possible for the centre to inhabit the centre.

But it is not weaving I am aiming to decentalise. It is protest and the requirement to be at centres of power for effective protests. At its most basic level decentralization is a process whereby a central hub is replaced by scattered interconnectedness, it is a neutral ideology. However, because it is a distribution method of goods and ideas, it involves power or power structures and is therefore not neutral. Politically it is championed by both the right and the left, with outcomes that are diametrically opposed.

My PhD could identify decentralisation methods that [textile] artists are already employing and investigate and use other methods in my own practise. It will also involve constraining and naming, building walls around concepts, creating categories within art activism and delineating protest textiles. Protest textiles are something that exist but are not yet a discipline. This field will be scooped out of existing practises, edges defined and an argument will be made for their importance and uniqueness.

So what decentralising methods will be employed?

Using mail and targeting allies will be tackled in the mourning arm bands project. When envisioning this project, the question was asked how to get feedback. Initially, it seemed unnecessary—it is protest, one does not get direct feedback. But with this project, that is different, it identifies and targets people within organisations that are construed as allies. If they are allies treat them as such, leave them a method of feedback, contact them to follow up. This project has a great research potential because of this ability to get information about direct results.

The two workshops will also provide for a chance for feedback. One of the projects, a quilt, will be craftivist, as in there is no direct targeted protest, the other, mourning accessories, will open up participants to direct protest. The mourning accessories will allow workshop participants to mail or give their crafts in protest, if they choose, along with the possibility for feedback from recipients. However, what the workshops will enable is feedback from participants. The participants will mostly be environmental historians, people who are much more concerned with climate change then the average person, so they are not a neutral study group, however, they are a good protest focus group because the craftivism will be more likely to motivate them, which is what the research will seek to answer in this project. How will participants change or think they will change their behaviour due to the workshop. Can workshops be an effective way to decentralise art activism?

Collaborating with an activist group will be investigated as a decentralising method. The idea is to make an art piece that is then used by activists in an action as they see fit. The caution tape project will be suggested, though not insisted as the collaboration. The ideal scenario would be to have around five different groups with the same or very similar art pieces and to see the various actions that each group comes up with. The activist groups will then be questioned to find out if the art changed their normal practise and if so how and weather or not this collaboration might change future actions. Having textiles and an art object will be key to this decentralisation method. A lot of art activism is anti-object (reference here) and textiles tend to be hyper object, it is the authority of the object that will be critical for this collaboration.

Centres of power can be travelled to for pop-up protests or protest events, while this is a method of decentralisation, a way to decrease the need to travel is to further the lifespan of the action by creating a protest afterlife. Performance protest weaving, where the act of creating is a part of the protest, will be created with intentionality to create effective protest ephemera to be exhibited afterwards. This project will take my concept of protest ephemera and develop it as an intentional outcome and seek to understand how this ideology can deepen art activism.

A huge decentralising force in our current society is social media. It is also a key element to craftivism. In the ice weaving project I will be adding to existing research in using social media to decentralise art activism. This project will investigate various spaces, poignant remote ones as well as everyday city ones, and use a combination of video and photography on social media as well as live for a performantive protest art installation.

Jelinek, A., (2013) This is not art: activism and other ‘not-art’. London ; New York, NY: I.B. Tauris.

Decentralising

Nandwani, B., (2019) Decentralisation, Economic Inequality and Insurgency. The Journal of Development Studies, 557, pp.1379–1397.

Mignolo, W., (2000) Local histories/global designs: coloniality, subaltern knowledges, and border thinking. Princeton studies in culture/power/history. Princeton, N.J: Princeton University Press.

Manor, J., (2006) Renewing the Debate on Decentralisation. Commonwealth & Comparative Politics, 443, pp.283–288.

Centres of Power

Butler, J., (2020) The force of nonviolence: an ethico-political bind. London ; New York: Verso.

Chomsky, N., Mitchell, P.R. and Schoeffel, J., (2003) Understanding power: the indispensable Chomsky. London: Vintage.

Rothe, D.L. and Collins, V.E., (2017) The Illusion of Resistance: Commodification and Reification of Neoliberalism and the State. Critical Criminology, 254, pp.609–618.

Gruber, L., (2000) Ruling the world: power politics and the rise of supranational institutions. Princeton, N.J: Princeton University Press.

Klein, N., (2008) The shock doctrine: the rise of disaster capitalism. London: Penguin Books.

Rancière, J. and Corcoran, S., (2010) Dissensus: on politics and aesthetics. London ; New York: Continuum.

Roberts, A. and Garton Ash, T. eds., (2012) Civil resistance and power politics: the experience of non-violent action from Gandhi to the present. Reprinted ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

March 2023: Part 2 of Creative Research Journal Mourning Armband

(See february for part 1)

My search for fabrics was long and moderately successful. I discovered due to the nature of website creation and search analytics, most fabrics that are listed on fabric store websites are not searchable. After discovering that one of my better fabric shops was entirely wholesale, I bought an approximation fabric from the tiny fabric shop in my town.

Armband prototypes

#1

armband #1 opaque crinkle polyester with double folded edging and velcro

-This prototype did not look good. My edges were huge and I do not sew very straight

did not look good.

#2: opaque crepe tubed with edges ironed after and velcro

-this seemed like it was going to be the best option. I had bought this crepe, the proper material for a mourning band and a translucent crinkled fabric. I was worried that my poor sewing skills would be too apparent on the translucent fabric. However, disaster struck and my sewing machine broke. The repair place said that fixing my old west German Pfaff was not worth it, it would be expensive and might not even solve the problem. This led me to buying a new machine and discover when disaster isn't disaster. My new machine is much easier to sew straight, which led to #3

#3 Opaque crepe with double folded hem edges and velcro

-This prototype uses significantly less fabric than #2, it also looked way better than #1. But #2 looked better. Conclusion: prototype #2 is best so far.

Testing Styles for lettering

Prototype #4 translucent crinkle fabric

Sizing

Lettering on Prototype #4

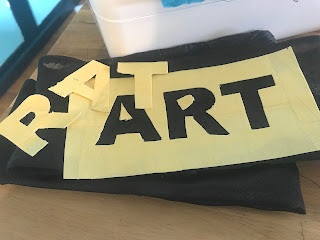

Some quick testing on spare fabric from prototype #4 made it apparent that a sewing machine could be used to create the lettering. The stretch stitch was not the most functional and the straight stitch did not end up impairing the stretch for fit. How see the lettering was more challenging. I picked a font I liked, determined the size and then printed it out. I cut out the letters and drew with chalk onto the fabric. It was way too difficult to see the chalk while sewing such particular small lines.

Masking tape stencil

I ended up cutting the letters out of layered masking tape, and then sticking the stencil directly only the fabric and sewing inside the stencil with my sewing machine. THe middle to the A & R I stick down in the approximate location and sewed around them.

Prototype #4: we have a winner!

This may be how the final product looks, it it may be that I use different colour thread for the lettering of ART.

February 2023: Creative Research Journal for Environmental Mourning

I watched a video of climate protesters throwing a can of soup at an artwork. I felt like their assessment of art in relation to climate change could have been cleverer. The video just sat with me for a few days, when I found myself needing to confront it. Was I against the action? The honest answer was sort of. As an artist, I did not feel outraged at the protesters for throwing soup at the paintings, though I am upset that the tomato soup did cause some damage because I like the work. The point I think the protesters failed to make or make well, but is incredibly valid and why I think the protest has some merit is that we, as a society, are heading towards making all art garbage by our inaction towards mitigating climate change. That in 50 to 100 years, with rising sea levels, climate refugees, food scarcity, etc, our society will collapse totally including galleries, museums and their collections unless we take strong measures to mitigate the disaster. But I am still not that keen on the soup throwing. But what could I do?

· Idea #:1 hold a funeral in a gallery for the artwork. What would work ideologically better than the soup protests would be to hold a funeral including possibly tiny versions of the artworks in the room. People come in black, weeping & wailing, have a eulogy for the dead art.

Pros:

- links art to climate change

- is something I would be willing to do

cons:

- small media attention. It would mostly just catch the attention of people in the room and maybe have a small reach outside of that

- the soup protests really got attention, shock & rage. The imperative of action was highlighted.

- has no proper target. It would be a lot more sensible to get the gallery to make some concrete changes but this would be unlikely to do so.

Conclusion: It would make a lot more sense to make a targeted action towards people in charge of the art galleries. It has the advantage that it is likely people who support better climate initiatives in galleries and thus it might actually result in some concrete changes.

· idea #2: mail mourning item along with pithy obituary or ueology (description of bizarre way the gallery died) to try to get galleries to enact concrete changes.

Pros:

- ideologically sound: a job of galleries is to preserve art and climate change makes this job a problem long term

- there is a tradition of gifting because it is harder to ignore a gift a lot of charities employ this method

- north west coast turtle island indigenous traditions because that receiving a gift comes with expectations. While this is not a western held view generally, there is something deep to this philosophy and held explain previous thought

- the audience I am addressing generally agrees with me and most (all? TBD) have held exhibitions on this theme

- it is plausible that some might take concrete action

- mourning the death of art is also funny because historically there have been periods when sections of the artworld bemoaned the death of art

- uses Alana Jalinek's theory that we all contain power, that the binary model, supported by the avant-garde and not yet lost, believes in the powerful versus the powerless, the good versus the bad is an incorrect assessment of power, that we all contain power, even artists. She further points out that even those who are convinced of human impact on climate fail to take actions to mitigate it.

- however, the other extreme is just as problematic. The zero waste movement is Neo-liberal bunk. It advocates that everyone has the personal ability to change the situation through their personal actions. It requires excessive money and time without tackling the real problem--that a majority of waste happens in the industrial, manufacturing and transportation phases long before it reaches consumers. That the time spent in trying to be zero waste could be better spent advocating for better practises that would then be available to average people and those with minimum wage jobs who no ability to be zero waste.

Cons:

- galleries have restrictions due to funding

- they are not the main cause of the problem

- will likely result in zero press coverage

- the action is so quiet that it may achieve nothing

conclusion: Pros outweigh the cons, it generally seems like it will be a good action.

What Form Should the Mourning Item Take?

My first instinct is that it should be a black armband like victorian armbands.

What already exists? There are "cause" ribbons wither in metal as depicted below or textile ones. There is also the wearing of poppies for war commemoration. Both of these have problems in that they are not specific enough.

There are also black armbands that are worn currently. They are most commonly seen on athletes, though military, police, fire, ambulance and politicians do wear them.

There are also specific black bands that are made and sold for covering badges of the police specifically, though images for military, fire and ambulance can be seen on websites that sell these black bands.

Requirements of the mourning item:

- It must be easily deciphered as a "mourning item" and therefore must be conventional

- It must be relevant today- ie:

victorian mourning jewellery with hair - It must be hand made

- It has to be relatively easy to make

- it must be black (see #1, non western galleries will not be targeted)

|

| Elasticized with velcro for military use |

|

| elasticized (non-velco?) available as large orders |

|

| a thin black ribbon that is just tied |

|

| military black armband in crepe |

Traditional victorian armbands are made of crepe. But crepe is a fairly non-specific material. It can be translucent with a pronounced foldy texture, which is what my mind envisions. It can also be a much less-pronounced textured opaque material. The image above is from a military apparel website that is selling a crepe black mourning band where the image is only an unspecific variegated black, but appears to be opaque and not crumply/foldy of my imagining. Further images from easy googling are not of quality, size or quality to give any definitive answer. The image on mourning armbands on wikipedia appears to be opaque slightly textured crepe, but even that is a guess, the picture is just too small and soft focused. My supervisors have recommended that I read Lou Taylor's book Mourning Dress as a good place to start looking for either mourning armbands or references that might have them. I haven't found the an online book that I have access to and the book isn't cheap. I did ask a librarian. Unless he finds an online copy that LJMU can gain access to, I do not think it will be timely enough for me.

Hopefully I get an answer to my questions. In the mean time I am trying to track down fabric like the bristol museum piece so that I can start to fabricate samples. The fabric is called plisse crepe.... but I live in Germany and this term is mostly not used, plisse translates into not just pleated, but pleated blinds. But there seems to be a wholesale fabric store near me that sells something that looks okay, though not translucent. It is called a musselin, which I take to mean muslin though it certainly could mean bot in German... I am not a fabric expert, so trying to get the correct fabric in a different language is proving a bit challenging. There is also crepe de chin and crepe georgette, which I think is more the opaque style I think I see. I will have to start figuring out where there are decent fabric stores near me, the one in my town is itsy-bitsy and unlikely to have anything like what I need.

January 2023: Searching for Solid Ground

caution tape test #1: a rolling fail

Caution Tape trial #2: it worked!

using gridding from a hardwear store. The background in the photo is actually from the piece above (it was white, so I used it). The work is complete with finished edges, it wants to bend or curl just a little bit. The lettering isn't quite as good, but I am very pleased with the overall look of it.

November 2022: Ice Weaving experiments in NYC

In November we had a transart residency in New York. I had signed up to do a skill share and intended to have the group make ice weavings--a project that I am doing as part of my PhD. I have told that there would be 26 people, which I was concerned would be too many people, so we made it sign up and almost no one signed up, so I cancelled the event. I was then left with a bunch of tiny ice frames. The size meant that they were too small to act in situ as protest. As a workshop, the small size would be fine, they would also be amplified by having participants post them to social media. They would be somewhere between a workshop and an online protest. But to quote Gil Scott Heron "The revolution will not be televised, the revolution will be live". I will add avoid the seduction of photographs ( a few photos make the work look piece). What the work is, if they are final pieces, is a quiet message with online amplification--in essence craftivism. It is possible to make photos that give an epic proportion to these small ice weavings, but Gil Scott Heron is correct, that protest functions best live, that the pedestrians should be favoured over the internet viewers.

other lessons learned: It is more challenging than anticipated to hang the work & there is way too many security guards in NYC (which also limits work placement).

Ice Weaving: Share the Road. 2022, 15 cm x 30 cm. Cardboard, hand dyed wool, heat, ice, time

Ice Weaving: Reporting a Climate Emergency. 2022, 20 cm x 30 cm. Cardboard, heat, ice, repurposed clothing, time.

Ice Weaving: On The Bridge. 2022, 15 cm x 35 cm. Cardboard, hand dyed wool, heat, ice, time.

Ice Weaving: Seeking Justice. 2022, 50 cm x 30 cm. Heat, ice, plastic, styrofoam, time.

Ice Weaving: Engulfed by the Judicial Institutes. 2022, 15 cm x 15 cm. Heat, ice, repurposed clothing, styrofoam, time.

Ice Weaving: Caution, No Justice for the Climate. 2022, 15 cm x 30 cm. Heat, ice, plastic, styrofoam, time

Ice Weaving: Reporting a Climate Emergency. 2022, 20 cm x 30 cm. Cardboard, heat, ice, repurposed clothing, time.

Ice Weaving: On The Bridge. 2022, 15 cm x 35 cm. Cardboard, hand dyed wool, heat, ice, time.

Ice Weaving: Seeking Justice. 2022, 50 cm x 30 cm. Heat, ice, plastic, styrofoam, time.

Ice Weaving: Engulfed by the Judicial Institutes. 2022, 15 cm x 15 cm. Heat, ice, repurposed clothing, styrofoam, time.

Ice Weaving: Caution, No Justice for the Climate. 2022, 15 cm x 30 cm. Heat, ice, plastic, styrofoam, time

Ice Weaving: Cityscape I. 2022, 15 cm x 20 cm. Hand dyed wool, heat, ice, styrofoam, time.

Ice Weaving: Melting Crosses Cultural Boarders. 2022, 20 cm x 50 cm. Heat, ice, plastic, repurposed clothing, styrofoam, time.

October 2022 : The Work begins

My month started out with my first supervisor meeting. I have two advisors through trans art, Leah Decter and Lynn Setterington. In this meeting, we introduced ourselves, the work we do, agreed to work together and it was suggested by both of my supervisors to alter my research focus/ questions. They suggested that my intended research into non-western protest textiles would not be a good topic for a PhD, though it might be used in the future. So then I was left with what are my research questions and what will I focus on, the plan was to stay with protest textiles, but re-frame it.

I was also applying to a Canadian SSRC scholarship at the time, so I wrote up the following proposal that includes my new thinking. The proposal makes no mention of the practise based element of my research as this was recommended to me to be the best method. The methodology of research through practise, or knowing about protest textiles by making protest textiles is therefore not mentioned in this write up.

My main objective is to categorize different types of protest art, something that as far as I can tell, has not yet been done, though I will mostly be doing this with textiles which certainly has not been done.

Britta Fluevog’s PhD Proposal Subversive Textiles: A Look at Protest Fibre Art

Introduction to My Research Questions

In September 2022, I started a three-year Doctorate of Philosophy program in Fine Art at Liverpool John

Moores University. My supervisors are Dr. Lynn Setterington, Dr. Leah Dector and Dr. Lee Wright.

My research aims to answer the questions: What are protest textiles? What are the different ways that art

and fibre functions as protest? And, how do protest textiles and art relate to broader social movements?

Our current era will likely be remembered as a period of civil unrest and mass demonstrations

throughout much of the world. Along with these protests are many artworks, playing different rolls. Now

is the time to investigate how art has functioned within a protest or political movement. Within my

research I am focusing on fibre art or textiles, such as the pussy hats at the 2017 omen’s March in the

USA. What are the strategies protest textiles have used and what does art have to offer to the field of

protest that is unique to art. What are subversive textiles and how are they used?

Existing Research

The Subversive Stitch: Embroidery and the Making of the Feminine (1984) by Roszita Parker is the first

recognized text that frames textiles within a political or activist lens. Parker’s research does not garner

much further writing until the do-it-yourself (DIY), internet, craftivist movement starting around 2002,

which can be traced through writings of Betsey Greer, the main founder of the movement. The deeply

political aspect of textiles is explored in The Empire of Cotton: A New History of Global Capitalism

(2014), by Sven Beckert, which explains the large roll textiles had within colonization. Activist and

protest textiles are discussed in Julia Bryan-Wilson’s Fray: Art + Textile Politics (2017). The most

similar research to my own work is Julie Decker and Hinda Mandell’s book, Crafting Democracy: Fiber

arts and Activism (2019), but this text is more of a historical framework than my research will be.

Craftivism as Key Cultural Context

My research examines the relationship between craftivism and protest. While craftivism is the

portmanteau of the words of craft and activism, I am viewing it through Tal Fitzpatricks’s reframing of

the term, specifically the changing of activism to DIY citizenship or civic engagement. So, while

craftivism can be found at intersections of ideology, history, educational guides, etc., it runs more

parallel to protest textiles rather than residing within or overtop of it. Certainly many activist (rather than

simply DIY citizenship) textiles have come out of the craftivist movement, but most craftivism is more

concerned with civic engagement than protest. Craftivism is very important to protest textiles, but it is

just a small facet to a much larger discipline that I am researching. My research will define and trace the

history of craftivism and discuss why not all textile protests fall within field of craftvisim.

Objective

The texts of existing political activist textiles will be threaded into general protest art ideology such as

found within TV Reed’s book The Art of Protest: Culture and Activism from the Civil Rights Movement

to the Streets of Seattle and Stefan Jonsson’s article The Art of Protest: Understanding and

Misunderstanding Monstrous Events. The this amalgamation of protest theory of the textile art will be

interspersed with various cultural theorist, when pertinent. Intersectional ideology will come from of

Kimberle Crenshaw and Bell hooks. Noam Chomsky and Naomi Klein will provide ideology on our

current western governance system and the necessity of activism, the artworks themselves can be

disseminated using Adorno’s aesthetics theories.

Protest art is usually categorized by medium, or different political movements, or what is being

protested. My research will also categorize different types of protest textiles in terms of how they

function within a protest: Personal or Community identity as a form protest like the Molas created by the

Kuna indigenous people of Panama’s San Blas Islands; artwork used within traditional protests such as

the banners at the Greenham common women’s peace camp; artworks where the art is the protest like the

arpilleras the Chilean women made against the dictator Pinochet; art that is the theoretical underpinnings

of a movement such as Khadi cloth was for Mahatma Gandhi and the Indian National Congress; artwork

that sits somewhere between political and protest, where the protest is more subtle like Kawira

Mwirichia’s Kangas celebrating African LGBTQ heroes; and peripheral artwork like artwork made about

protests or artwork from protests that is subsequently exhibited in new contexts and what these

peripheral actions can mean.

Methodology and Expected Outcome

My methodology and expected outcome are somewhat commensurate. My research will find, categorize

and analyze different types of protest textiles with the intent of being informative to those who wish to

study the subject and elucidating to those that want to create them. Categorizing will allow parallels to be

made on how the different textile art functions within a protest or a political movement. My research

uses Empirical Analysis and Exploratory Analysis to understand differences between the different

categories.

Within the categories my research will provide examples of around two five different artworks or art

series or connected art that demonstrate the particular category of protest art well. The artists or groups

researched will be varied in many ways, with the intersectionality being an integral foundation within the

research. Some art will be well researched, with large bodies of literature to draw upon while others will

be relatively obscure where the artwork will be required to speak more for itself. A global approach will

employed with textiles from diverse countries and communities within them.

Many of the books on activism and textiles are edited collections of essays and as such have a very broad

viewpoint as well as broad definition of activism—this promotes inclusivity, but it does water down the

notion of activism or protest. Lots of research, such as most craftivism, has focused on political textiles

that are quiet, polite fibre works, which admittedly is something that fibre excels at, but is not the

exclusive usage of them. My research will focus more on the brash and unapologetic textile work,

because as I aim to shown, there is value in being loud while protesting like Marianne Jorgensen’s pink

yarn-bombed tank, Pink M.24 Chaffee Tank (2006).

The main argument of my thesis will be that these categories exist and that dividing protest art into

different categories will be useful. My research will analyze and compile previous analysis, but a main

focus of my research will be to initiate further artwork and research within the field of protest textiles.

My Motivation

My research reflects who I am as a person and that is why I do the work. I am a textile creator and an

activist. Through the work of my research, I aim to improve both of these aspects, both for me personally

and for my peers.

*******end of paper*********

This month, I have also started doing some writing on craftvisim, ordering and reading literature.

I have also been working on a very large waffle weave. I built/set up the loom and am in the process of spinning and warping it. My re-framing of my thesis has been useful because it led me to a greater understanding of this piece. The last few works I have been making are about personal identity as a form of protest.

No comments:

Post a Comment